Living Root Bridgte, Meghalaya, 1999. Animation. Photo by Anselm Rogers.

Reader Architecture

The ecological crisis is a crisis of materiality. Since the advent of concrete as a (Western) building material, our common world has been getting grayer by the minute. As with plastic, we are only now waking up to its dangers. We need to use materials that are embedded, that build on the interconnectedness of all life and its re-creation.

By Xinatli Collective

Published May. 14, 2021

In the time it takes you to read this sentence, the global construction industry will have poured more than 19,000 bathtubs of concrete (The Guardian, 2018). In a single year, this is enough to patio over every hill, dale, nook, and cranny in a country the size of Ecuador. After water, concrete is the most widely consumed material on the planet. We use it for buildings, bridges, dams, and roads. We walk on it, drive on it, and many of us live, sleep, and work within its walls. Concrete: the foundation of Western modernity. A key to urbanization. An attempt to tame nature and defy its elements. But all the alleged comfort, easy upkeep, security, and convenience comes at a huge cost. Concrete lays not only the foundation for separation from the natural world but is also one of the most destructive materials on Earth.

The production of concrete consumes enormous amounts of energy. If concrete were a country, it would rank third in emissions behind China and the United States, accounting for around 8% of global carbon emissions (The New York Times, 2021). Moreover, concrete is a thirsty behemoth. By sucking up almost 9 % of the world’s industrial water use contributes to strain on drinking and irrigation supplies. In the coming decades, 75% of this consumption is forecast to occur in drought and water-stressed regions (Nature, 2018). In urban landscapes like Mumbai or Mexico City, concrete also adds to the heat-island effect by absorbing the warmth of the sun and trapping gases from car exhausts and air-conditioner units. And though light-colored concrete can reduce this effect due to its higher albedo, vegetation offers even greater benefits. Why not walk barefoot on grass in a city?

The Metropolitan Area Outer Underground Discharge Channel (Japanese: 首都圏外郭放水路), is an underground water infrastructure project in Kasukabe, Saitama, Japan. It is the world's largest underground floodwater diversion facility, built to mitigate overflowing of the city's major waterways and rivers during rain and typhoon seasons. Photo by Dddeco.

The world is running out of sand

In addition to its intensive production processes, concrete is an extremely rigid material composed of cement, water, stone, and sand—and the world is running out of sand. But what of the oceans of sand in the deserts? Unfortunately, that’s the wrong kind of sand for construction. Consider the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, the world’s tallest skyscraper. Despite being surrounded by sand, it was constructed with concrete made of sand imported from Australia.

This is because wind action in deserts results in rounded grains that are too smooth and too small to bind well in concrete. The sand the building industry needs is the angular stuff found in lakes, on beaches, and in the beds, banks, and floodplains of rivers (BBC, 2019). The demand for that kind of sand is so intense that riverbeds and beaches are being stripped bare worldwide, and farmlands and forests are torn up to get at the precious grains.

In a growing number of countries, criminal organizations have moved into the trade, spawning an often lethal black market. The Mexican environmental activist José Luis Álvarez Flores was murdered in June 2019 after receiving death threats for denouncing the illegal extraction of sand from the Usumacinta river (El Universal, 2018). Four people were killed in eastern India as villagers protested sand mining in 2017 (Reuters, 2017). According to human rights groups, children in parts of Latin America and Africa are being forced to work in sand mines.

The geosocial impact of concrete

Finally, let’s touch on the least severe and least-understood, impact of concrete: the psychosocial impact. “Concrete is more than a material. It’s about life,” claims the male-dominated Global Cement and Concrete Association. The direct opposite is the case. Unlike “life” or the natural world, concrete does not grow, exchange or interweave with its surroundings. Instead, its chief quality is to harden. The material creates rock-hard structures and is therefore destined to create rock-hard ways of being. Concrete entombs vast tracts of fertile soil, constipates rivers, chokes habitats, and desensitizes from processes outside the urban fortress. Civilizations once intertwined with nature follow the paradigm of progress to become aspiring superpowers of the 21st century and economies obsessed by GDP statistics and production rates. This transformation requires mountains of cement, beaches of sand, and lakes of water.

In a concrete culture that engulfs most modern humans, we live in separation from the world and seek certitude through control, including control and subordination of the natural world. In this respect, concrete is a crime against the future. because the material doesn’t nourish a structure’s potential for transition or an understanding of life, not based on domination and hierarchies but respectful of the relational fabric of all that lives.

The mother of all construction materials

There are alternatives. Earth is the mother of all construction materials. It is environmentally friendly, and humans have been using it ever since starting to settle. When an earthen construction is demolished, the earth returns to the soil and can be reused and reintroduced into cycles. It is there at our feet, in the ground, as humus, in essence as a kind of natural cement for a more humane way of building. Building with earth makes ecological sense but is still considered, in the perspective of the global north, as unstable and primitive—a building material for the poor. Not modern. But the destruction caused by eurocentric modernity needs solutions that are nonmodern.

We need a reorientation from the functionalist, rationalistic, and industrial traditions of theWestern modernity, towards traditions of wisdom that cherish a type of rationality and set of practices attuned to the relational dimensions of life, the richness of placed-based knowledge. “African architecture should stop copying the West, engage the real needs of the people and regard the environment,” says the architect Diébédo Francis Kéré, one of the innovators of earthen architecture.

The architect Mariam Kamara is also shedding dominant norms to set more relational precedents. Breaking away from architectural standards that correspond to Western ideas as if they proclaim a universal truth about building, she is developing a practice rooted in the rich building culture of Niger and seeking answers to its social, climatic, and cultural challenges. “Essentially, it is about simply looking at how we live in Niger,” Mariam Kamara explains in an interview with African Mobilities.

Kamara's first project, "Niamey 2000," was realized with her Iranian colleague Yasaman Esmaili: six two-story residential units for the middle class in the rapidly growing capital Niamey—made of clay bricks. Used wisely, earthen constructions are stable, promote the local economy, and regulate the indoor climate excellently in a place where temperatures climb up to 45 degrees. The windows of "Niamey 2000" are tiny embrasures—for protection from the glaring sun and because privacy is defined differently in the Muslim country. There is light and openness in inner courtyards, which belong to the apartments.

Building practices based on traditional ecological wisdom

Building with Earth is not only a choice of material but a worldview of embeddedness within the earth as a life-sustaining system. The wisdom traditions, including those of indigenous peoples, are a partial guide towards constructing models based on symbiosis.

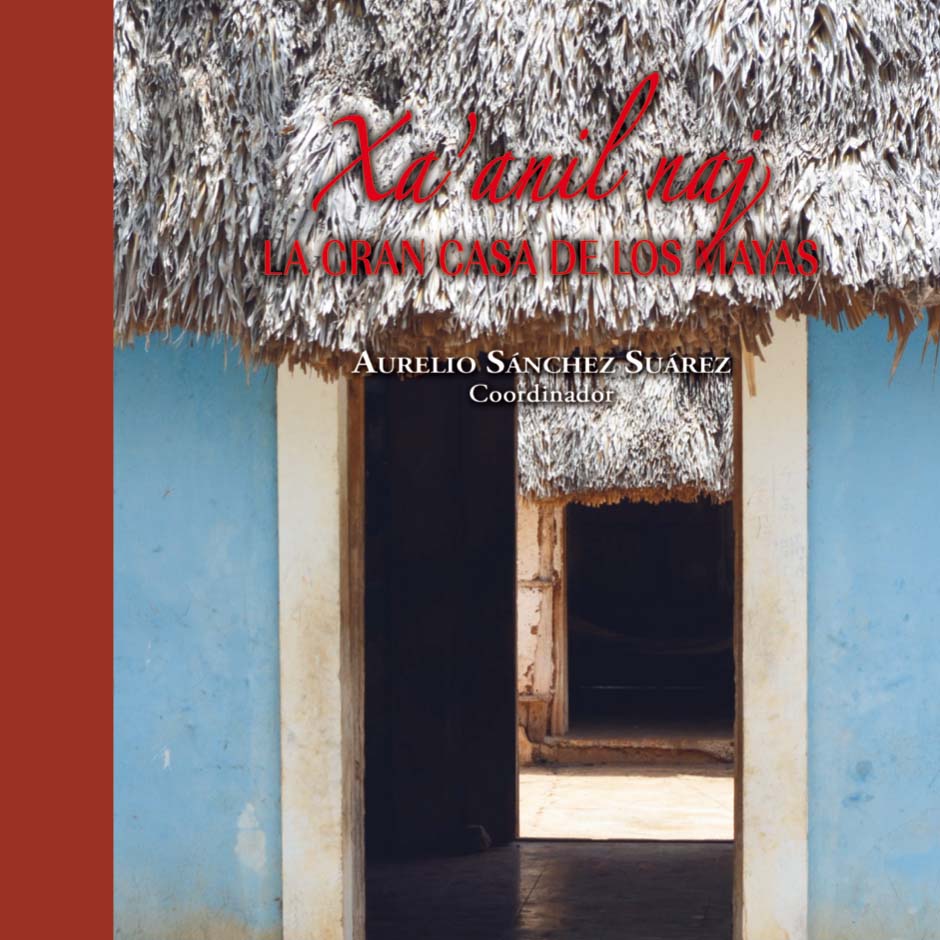

The Mayan dwelling, the xa'anil naj (house of guano), excellently illustrates this. A combination of trees and vines symbolizes a mountain, but they are also the structural elements of the house. The trees are transformed into pitchforks, and instead of being laid, they are planted; likewise, the house is not nailed, screwed, or glued; the house is tied. The relationship with the environment is different from the western conception of property. Every place is sacred. People don’t own the land as property. People belong to the land.

Aurelio Sánchez Suárez. Xa'anil naj. La gran casa de los mayas. 2018.

Planting a waffle garden: Zuni Pueblo, New Mexico. Museum of New Mexico. Photo by Jesse Nusbaum, 1911.

Sustainable agricultural practices also help conserve biodiversity. The Milpa system in Mexico uses a cycle of burning, mulching, and fallowing to promote forest succession, soil fertility, and polyculture gardens. The Zuni people developed the waffle garden design, which is still used today as an ecological method of water conservation. In Tanzania, the Kihamba forest gardens of the Chagga people support over 500 species by intercropping trees with agriculture.

For 500 years, the monsoon caused streams in the mountainous rainforest to swell into raging torrents, cutting off villages from the outside world. So the Khasi people began to weave the roots of the trees along the banks of the streams, and over the decades they built strong, wide bridges that could be crossed with dry feet.

These structures typically become stronger with age and can survive for centuries. They regularly withstand flash floods and storm surges, and are an inexpensive and natural way to connect remote mountain villages scattered across steep terrain.

Where concrete is patriarchal, subordinate, and creates hierarchies between nature and culture, human and non-human, building with earthen materials is non-hierarchical, sustainable, and reminds us of the ongoing ecological interconnectedness that allows and encourages human and more than human communities to thrive.

Living root bridge. Photo by Ahinsajain. CC By 2.0 [Creative Commons]

xinatli – museo de investigación artística

xinatli is an artist-led initiative that seeks to spark new discourses, and ultimately build plattforms that advocate for greater ecological and social equity.

general information

info@xinatli.org

media enquiries

communicacion@xinatli.org

funding & cooperations

proyectos@xinatli.org

this is an artist initiative. we use no cookies nor tracking.

mixed media

for project descriptions, sketches, images, press releases. » see more